This site highlights an ongoing project concerning the Armenian diaspora communities worldwide. It represents only a small percentage of the material that have been catalogued. For each country/region, there is a brief history, a map selected randomly, and 10 entries also selected randomly.

Quick background:

Armenian-Iranian communities (in Armenian: Iranahay/Parskahay) were formed in two points of history as the result of two imperial wars: the first one took place in the early 17th century and the second one in the early 19th century.

The first war opposed the Ottoman Empire and the Safavid Kingdom of Iran over the eastern provinces of Armenia. To stop the advancing enemy, Shah Abbas I of Iran implemented a scorched earth policy in 1604-1605. The policy involved the destruction of Armenian towns and villages and the mass deportation of the population to Iran's central regions. The city of Joulfa, the Armenian international trade hub, was demolished. Many deportees perished due to starvation, epidemics and exhaustion. The majority of the survivors were resettled in the imperial capital Isfahan and its surrounding rural areas (Peria, Boulvari, etc.), and the rest were resettled in central and northern provinces such as Hamadan, Qazvin, Arak, Guilan and Gorgan.

The second war opposed the Qajar Kingdom of Iran and Tsarist Russia almost two centuries after the first conflict, again, over the eastern provinces of Armenia. According to the treaty that concluded the Russo-Persian War of 1826–28, the Qajar Kingdom ceded its Caucasian territories, including modern-day Armenia, to Russia. The new border between the two empires was set at the Araxes River leaving two Armenian provinces south of the river within Persia. The population of these two regions gradually shifted to urban centers and sizable Armenian communities emerged in the provincial capital Tabriz, and in cities such as Urmia and Maragha.

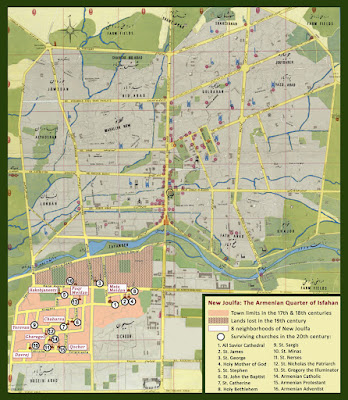

Map:

Map of Isfahan (early 1950s) modified to show the evolution of New Joulfa from the 17th to the 20th century. Following the deportation of 1604, Shah Abbas I Safavid resettled the wealthy merchants of Joulfa in his capital’s southern suburb that he named New Joulfa. The streets were named after the most prominent merchants. The main avenue was named after Khoja Nazar Shafraz (Safrazian). Thanks to the support of Shah Abbas I, New Joulfa soon became the hub of one of the greatest trade networks of the early modern era and an important cultural center.

In 1658, under the reign of Shah Abbas II, the Armenians who had been resettled within Isfahan were expelled to New Joulfa. Thus new neighborhoods were created to the south, some of which bearing the names of ancestral cities such as Yerevan and Tabriz/Davrej. Overall, New Joulfa got 8 neighborhoods. It was a walled city with 33 gates.

The decline of New Joulfa came with the fall of the Safavid dynasty. Additional taxes, sporadic pillages, confiscations, pressures to convert, and other types of discriminatory practices placed the community in jeopardy. Most of the finest mansions of New Joulfa (north of Nazar Avenue) were destroyed during the Afghan invasion of 1722. In 1796, the capital was transferred to Tehran. New Joulfa gradually shrank. Reza Shah Pahlavi demolished the city walls and gates in the 1920s. From 24 Armenian Apostolic churches at the end of the 18th century only 13 remain standing today.

1.

First two pages of Détails sur la situation actuelle du royaume de Perse (Details on the Current Situation of the Kingdom of Persia) by Mir Davoud-Zadour de Melik Chah Nazar, published in Paris in 1817. The trilingual book, in Armenian, French and Persian, was authored by the Envoy of His Majesty the King of Persia. Davoud-Zadour Melik Shahnazar (portrayed on the left side), Knight of First Class of Order of the Sun and the Lion (depicted on the right side) was an Armenian-Iranian diplomat born in New Joulfa, Isfahan. He served both the Persian and the French courts between 1802 and 1818 (during the reigns of Napoleon Bonaparte and Louis XVIII of France), including in the delicate period of 1811-1815 when diplomatic relations between the two countries were broken off.

2.

Internal View of the Dome of Holy Bethlehem Church, 2017, Mir Saeed Hadian. Built by Khoja Petros Velijanian, the church is one of the most important historical churches of New Joulfa. It has the most richly decorated dome. Since the facades of Safavid mosques were lavishly adorned, the New Joulfa church facades had to be plain by contrast to avoid any impression of competing against mosques. The architects therefore designed church interiors with richly decorated frescoes and tiles to compensate for their bare facades. This was a complete reversal in the Armenian tradition of church building. The amount of interior decoration depended, of course, on the financial capabilities of the sponsor. At the time, there was a fierce competition among the leading merchants to build the “most sumptuous church” but the church interiors show that there were important disparities in their wealth.

3.

Portrait of Armenian Woman, date unknown, Antoin Sevruguin. A. Sevruguin (1851-1933) was the most celebrated photographer of the late 19th century Iran. He established a studio in the capital Tehran in the early 1870s where he produced a large body of work. He was also appointed an official court photographer after which he became to be known as Antoin Khan. He was a photographer who had no boundaries in portraying people of all social classes and ethnic backgrounds. In a career that spanned over five decades, Sevruguin recorded Iran in all its facets.

4.

The Virgin Mary and Child, early 20th century, tile, private collection. Armenian-Iranian craftsmen combined Persian art and craft with Armenian-Christian traditions and created new styles in carving, ceramics, painting and mosaic art. Their work decorated extensively the Armenian churches and the mansions of the wealthy merchants of New Joulfa, Isfahan.

5.

Aibeta Café and Chocolatier, 1967, photographer unknown. One of the first confectioners of Iran, Aibeta was founded by Ms. Nazik Aidinian and her husband, both Armenian refugees from Russia. Some Armenians of Russia and Ukraine fled to Iran in the early 1920s, following the Bolshevik Revolution. Many went into food and beverages, hospitability and restaurant businesses. Aibeta and other Armenian-owned cafés were radically different from the traditional Iranian teahouses/cafés (in Persian: ghahve-khaneh): The guests were seated around tables; there was a menu to choose from; the food was served on individual plates and consumed with forks, spoons and knives; and there was usually a stage for live music.

6.

Cinema, theater and television actress Irene Zaziants (1927-2012), commonly known as Irene, is considered Iran’s first female “movie star.” She played in both mainstream and so-called art-house films, sometimes in controversial and nontraditional roles. She was the first Iranian actress to appear in a bikini in a film (The Messenger from Heaven directed by Samuel Khachikian, 1959). After the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Irene was banned from acting and became an esthetician.

7.

Khachatour Kesaratsi (1590-1646), the Archbishop of New Joulfa, was the founder of the first printing press in Iran (and in the Middle East). The first book Saghmosaran (Psalter) was printed in 1638. Since the Safavid era, Armenian-Iranians have contributed significantly to the overall configuration of the Iranian economic and cultural life. They are accredited with many “firsts”: the first printing press, film, theater, nursing home, leather processing factory, potato chips factory, fast food establishment, etc. The feeling of being a pioneer of modernity gradually became an important element of the community identity. This self-perception has survived to this date even though non-Armenian Iranians (Persian Muslims, Jews, etc.) excelled as modernizers in second half of the 20th century.

8.

A street sign indicates the direction to the Baron Avak neighborhood, 2016. Baron Avak or Barnava/Barnavak (corrupted form in local Azeri-Turkish) is a neighborhood in central Tabriz, the capital of Azerbaijan province. It used to be an Armenian neighborhood stretching between Lilava/Leylabad, another Armenian neighborhood, and Tabriz Grand Bazaar. Baron Avak Street and the surrounding neighborhood were constructed by Avak Avakian / Avag Avaguian in the late 18th century for poor and middle class Armenians of Tabriz and the recent migrants from the surrounding Armenian villages. The neighborhood gradually lost its Armenian inhabitants during the 20th century.

9.

The Students of Adab Armenian School Visit the Abadan Refinery, 1969, official school photo. Adab was the only Armenian school in Abadan. Following the discovery of oil in the southern province of Khuzestan in 1908, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company built the world’s largest refinery in the port city of Abadan. Armenians from cities such as Tehran, New Joulfa, Tabriz and the province of Chahar-mahal, moved to the south looking for job opportunities starting in 1909. Better educated than the locals and multilingual, they occupied mainly mid-level positions in the Oil Company. The parents of most of the students pictured here worked for the Oil Company.

A Group of Young Dancers Prepare for Zartonk’s Annual Performance, 2018, Adis Isagholian. Zartonk Armenian folk dance ensemble was founded in 1988 in Tehran after the Islamic authorities lifted some of the restrictions on dance and music. Initially, after the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, dance and music were totally banned in accordance with a strict interpretation of Sharia Law. Armenian dance schools such as the Folk Dance and Song Ensemble, founded by Sarguis/Sarkis Janbazian (1913-1963) went underground for a couple of years and eventually disbanded.