This site highlights an ongoing project concerning the Armenian diaspora communities worldwide. It represents a small percentage of the material that has been catalogued. For each country/region, there is a brief history, a map selected randomly, and 10 entries also selected randomly.

Quick background:

The vast territories north of the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea that comprise modern-day Ukraine and Russia attracted Armenian refugees looking for safe places to live throughout centuries. Armenians started to settle in the northern lands in the mid-11 century when neither the Russian Empire, nor even the Moscow principality existed. Given the date of migration (the century), the province of origin, and the demographics of the migrants (e.g. presence/absence of peasants, priests or nobles), distinct Armenian communities were formed. The economic possibilities of the land of refuge (e.g. absence or presence of international trade routes, fertile agricultural land) and the political, cultural and religious contexts (e.g. decentralized pagan Circassian villages in the North Caucasus, Muslim Tatar population ruled by the Byzantine Empire in Crimea) also determined the "type" of Armenian communities that developed.

With the territorial expansion of the Russian Empire southward and westward starting in the late 17th century, Armenian communities were gradually absorbed into the Empire. By the early 20th century, prior to the Bolshevik Revolution, several Armenian communities; each with distinct history, dialect and set of customs existed. The Soviet Union standardized these sub-cultures and despite its proclaimed goal of forging a “brotherhood of nations,” embarked upon the assimilation of Armenian communities.

Map:

Map of Armavir (Kuban Region, Southern Russia), 1913. The map shows the Armenian community institutions (3 churches and 2 schools) and most but not all of the factories owned by Armenian entrepreneurs. Due to its high degree of industrialization, Armavir was informally called the “Manchester of the Kuban Region” prior to the Bolshevik Revolution. Named after the historical capital of ancient Armenia, the town was founded in 1838 to allow the Mountainous Armenians or the Armenians of Circassia (in Armenian: Cherkezahay) to abandon Circassian settlements, to move down to the Kuban valley and to be urbanized. The Armenian-Circassian communities were formed in the mid-11th century. Not much is known about their history.

Established in 1815 by Hovakim Yeghiazariants/Lazarian thanks to funds bequeathed by his brother Hovhannes/Ivan, the Lazarian Institute was initially an Armenian primary school for the community based in Moscow. The school later expanded to include secondary education, a translation center, a publishing press, a theater, and eventually higher education and academic research focused on eastern and Caucasian studies. The Lazarev/Lazarian Institute played a fundamental role in revitalizing the Armenian-Russian communities in the 19th century through training leaders and staff (teachers, journalists, priests, etc.) for community institutions.

The New Nakhijevan Dramatic Theater was designed by architect Nikolay Durbakh (Nikoghos Durbakhian) (1858-1924) and inaugurated in 1899. Plays were staged in Russian and in Armenian by local and visiting troupes. Now it is called Rostov Regional Academic Youth Theater. New Nakhijevan was a city that the Armenians who had been forced to migrate from Crimea in 1778 founded on the shore of the River Don, next to the Rostov fortress. Named after the Armenian province of Nakhijevan (now part of the Republic of Azerbaijan), the city was also called Nakhijevan-on-Don. The new settlement quickly became a prosperous city of artisans and traders. In 1928, the Soviet authorities renamed it Proletarian District and merged it in Greater Rostov-on-Don.

3.

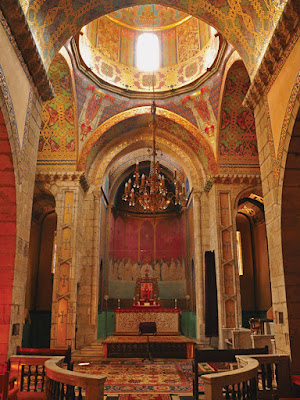

The dome of the Armenian Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary, Lviv/Lvov, Ukraine. Indisputably the most elegant Armenian monument in Western Ukraine, it was built in 1363 and served as the regional center of the Armenian Apostolic church. In 1630, its clergy converted to Catholicism and turned the temple to the seat of the new eparchy of the Armenian Catholic Church. All the other Armenian churches in the city were confiscated and most of them demolished after 1772 when Lviv was annexed by the Austrian Empire. After the Second World War, due to the westward shift of borders, the city was included in the Soviet Union and the Cathedral was confiscated. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian authorities gave the Cathedral “back” to the Armenian Apostolic Church in 1997 under the condition that the Armenian Catholics, now mostly based in the neighboring Poland, would also be allowed to use it.

4.

Mikayel Nalbandian, date and photographer unknown. Writer, poet and political activist M. Nalbandian (1829-1866) was a pioneer of the Armenian enlightenment movement from New Nakhijevan, Russia. For him, agriculture was the key towards economic freedom and prosperity. He published his main work on political economy; Agriculture as the True Way in Paris in 1862 in which he advocated the equal redistribution of land as a measure of social justice. Nalbandian’s book was published under a pseudonym so the Russian authorities did not notice it immediately, but his contacts with Russian revolutionaries did not go unnoticed. Nalbandian was opposed by the Armenian conservatives, was persecuted by the Tsarist authorities, and eventually died in prison. One of his poems; The Song of an Italian Girl, inspired by the Italian unification movement, was adopted by the government of the First Republic of Armenia (1918–20) for the country's national anthem. The anthem was reinstated in 1991 with some changes.

Portrait of Anna Bournazian, 1882, Ivan/Hovhaness Aivazovsky, oil on canvas, Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia (73 cm x 62 cm). She was the painter’s second wife. He said that by marrying Anna he became "closer to his nation." Ivan/Hovhaness Aivazovsky (1817-1900) was one of the most fascinating and richly talented artists of the 19th century and is one of the most prominent Armenian-Russian figures of all times. He was from Crimea. He left behind an astounding collection of 6,000 paintings, mostly magnificent seascapes.

Anastas Mikoyan (in the middle) with Stalin (on the right) at Lenin Mausoleum where big parades used to take place. A. Mikoyan (1895-1978) was several times Minister, Vice-Primer, First Vice-Primer and the President of the USSR. He managed to remain in power for four decades despite the purges, upheavals and disasters that befell the USSR. His extraordinary longevity can be seen through the pictures at Lenin Mausoleum where he stood beside different leaders including Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev.

Armenians and Tatars in a Café in Karasou Bazaar, Crimea, 1837, Auguste Raffet, lithograph. Russian Count Anatoly Demidov who accompanied Auguste Raffet, the French painter, to Crimea wrote; “squatting on the couch that surrounds a narrow space with a stove in the middle and a parade of slippers left on the ground, the Tatars and the Armenians spend hours smoking in silence their long cherry wood pipes.” (The Crimea, Count Anatoly Demidov, Paris, 1850).

Dancing around the fire at Saint Karapet Armenian Church in Yakutsk. The Terendez festival is a pagan-era celebration of sun worship that was later included in the Armenian Apostolic Church traditions. The ritual intrigues the indigenous people of Yakutsk who are predominantly pagan. Inaugurated in 2014, the church and the adjacent Saturday school serve the Armenian community in this eastern Siberian land.

General Valerian Madatov, 1820, George Dawe, oil on canvas, Military Gallery of the Winter Palace, Saint Petersburg. Born Rostom Madatian in the village of Avetarnots/Chanakhchi in Artsakh/Karabagh, Valerian Madatov (1782-1829) was a general of the Imperial Army and a hero of the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878. An estimated 10 percent of generals and officers of the Tsarist army was Armenian (only 1 percent of the general population). Most of them participated in Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War and Russo-Turkish wars. Armenian servicemen came from various territories that made up the Tsarist Empire. A big contingent came from the Armenian-Georgian community. A considerable number were from Artsakh/Karabagh.

The Sorrow of Cleopatra, 1987, Arsen Savadov with Gueorgy Senchenko, private collection. Armenian-Ukrainian conceptualist photographer and painter Arsen Savadov (born in 1962) is one of the most creative and provocative representatives of Ukrainian contemporary art. The Sorrow of Cleopatra is considered the start of contemporary (post-Soviet, independent) Ukrainian art.